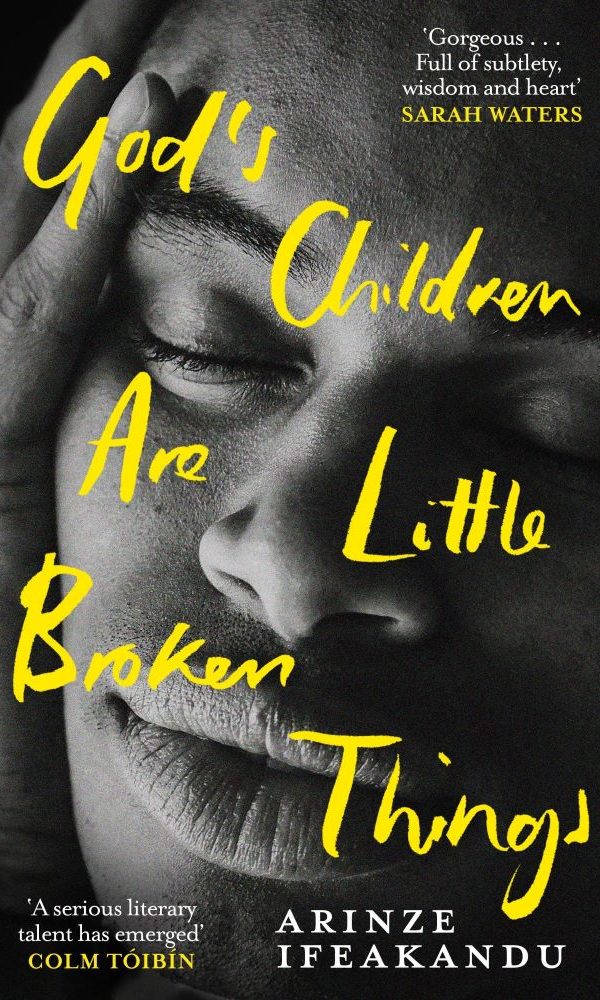

Arinze Ifeakandu‘s God’s Children Are Little Broken Things (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2022) won the International Dylan Thomas Prize in 2023. It’s a collection of nine short stories set in Nigeria—in Abuja and Kano, mostly—all of which have male queer stories at the heart.

In none of the stories is being queer straightforward.

Sometimes the difficulties arise from family you’re born into, such as in the final story ‘Mother’s Love’; at other times it’s a problem with being in a pre-existing heterosexual relationship, and therefore ‘in the closet’, as in the opening story ‘The dreamer’s litany’. In the masterpiece, ‘What the singers say about love’, capitalism and celebrity get in the way of Somto’s erotic fulfilment.

But there’s another phenomenon in almost all of the stories: language. Sometimes it’s a barrier; at other times it helps.

Languages in Nigeria

There are three main languages in Nigeria, belonging to their respective ethnic groups. About 30 per cent of citizens are Hausa (mostly from the north, such as Kano), and around 15 per cent of people are Yoruba (west).1 The same is true of Igbo (east). Many Hausa are also Muslims, so there are also modern religious differences as well as older ethnic and cultural ones.

To a British mind reading a text written in English, it is probably difficult to distinguish between writers of different ethnicities. Nevertheless, some major Nigerian writers have different ethnic backgrounds. For instance, Chinua Achebe—possibly the most famous Nigerian writer in English—was Igbo (pronounced with a silent ‘g’), just like Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie. Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, is Yoruba.

Added to these ethnic-based languages, English is also widely used, as is the creolised English, pidgin.

I think this is difficult for us in Britain to understand: these aren’t just regional dialects or riffs on a single language. They are different languages with different histories. It reminds us that Ifeakandu’s Nigeria is a heterogeneous nation—distinctive because there is no dominant culture, ethnicity, or language—whereas in Britain proper consideration of national or regional cultures is often softened by erased by a shared language.

No wonder language becomes an obstacle to the queer stories in God’s Children.

The language of love

In an interview on the PEN website, Ifeakandu said that

Language is an aspect of characterization, I think. We code-switch in order to feel safe or to communicate more effectively or to flex, or intimidate. Like the clothes we wear, our speech reveals, sometimes, our class. I used language in that way to show clearly the—sometimes—shifting dynamics between characters. Igbo, for example, is sometimes used for endearment, but at other times, it alienates, rebukes. Everything depends on context.

We see this in the opening pages when owner of a store Auwal, is visited by Chief Emeka. Auwal is surprised when Chief speaks Hausa because

he’d not expected Hausa to be, for this man, a language of tenderness, he’d expected it to be a language for business, a language to be used and discarded and reused.

Arinze Ifeakandu, ‘The dreamer’s litany’ in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2022), p, 3.

On one hand, a language of love; on another, it could be a useful language—an instrumental language with cold, objective purposes. In the course of the story, it becomes more of the former: ‘[T]he more Chief came to know about Auwal in that language, the more Auwwal wanted to share’ (Ifeakandu, p. 4).

The amazing thing for Auwal is that Chief uses it to woo him, ‘code-switching’ (to use Ifeakandu’s sociological term) from businessman to lover.

Insults and defiance

And yet, later in ‘The dreamer’s litany’, Auwal begins to fear Chief’s ‘insults, said in Igbo, that were particularly hurtful because he did not know what they meant’ (Ifeakandu, p. 6). Changing language can also be used as a weapon.

In ‘Happy is a doing word’, schoolboy Nnamdi defies his mother’s inquisition in Igbo about what he’d been up to with his male friend Binyelum. His defiance comes through by responding in English (Ifeakandu, p. 29). The language-switching stands in for what teenagers do around the world.

The use of Igbo by parents is repeated in the title story. There, Lotanna has been forced apart from his lover, Kamsi. Lotanna’s father gives him a lecture:

All this in Igbo, which you could not speak in a situation like that. Because you had very few Igbo words. You kept mute, kpịm, tapping your bare feet on the floor.

Ifeakandu, p. 88.

Interestingly, the narrator refuses to translate the Igbo word ‘kpịm’, demonstrating what it felt like for him to be lectured by his father. It removes his and our power; our power as readers is only active when we can understand the words on the page. Without that comprehension, we too are disenfranchised and disempowered.

Postcolonial queer languages

There is a certain eccentricity to God’s Children Are Little Broken Things because of the use of various languages. We are made aware that these stories, in English, hide many of their native language conversations.

We get the odd word or phrase, but never whole sentences. This is the off-kilter, eccentricity: we are set apart from the centre. The languages are queer, in both an ordinary and metaphorical sense.

This irony arises from the presentation of a native tongue to English speakers, which is, in fact, a translated language—one that has taken on the sense of colonial and centrist domination.

English is therefore also made eccentric, queered. This is evident in the text when, for example, Ralu notes his friend ‘Makuo’s earnestness [in] his use, completely, of English instead of pidgin’ (Ifeakandu, p. 111). I was reminded, here, of Tayeb Salih’s 1969 novel Season of Migration to the North in which, in Sudan, the narrator tells us that once the British have left,

The railways, shops, hospitals, factories and schools will be ours and we’ll speak their language without either a sense of guilt or a sense of gratitude.

Tayeb Salih, Season of Migration to the North, trans. Denys Johnson-Davies (London: Penguin, 2009 [1969]), pp. 49–50.

I’m not suggesting that this is definitely the case, but I think it’s worth exploring the queerness of a colonial language; or, at least, at how the queer narratives at the heart of Ifeakandu’s God’s Children also make queer other aspects of the narratives. This could include unsignalled postcolonial aspects of living in Nigeria.

- These data retrieved from the CIA website. ↩︎