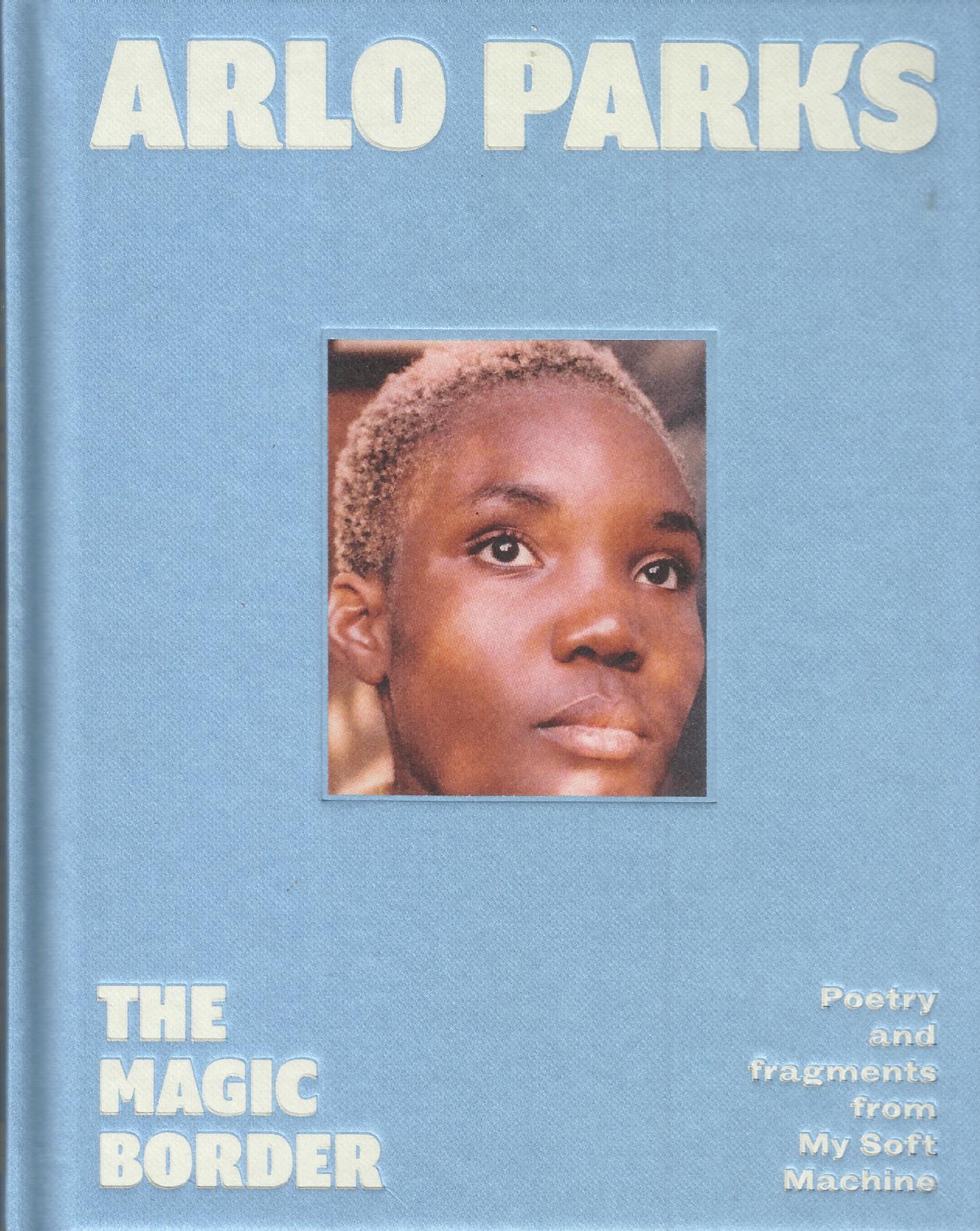

Arlo Parks

Arlo Parks won the Mercury Prize in 2021 for her debut LP Collapsed in Sunbeams (Transgressive Records). The Prize annually awards the album of the year, with no constraints of genre. On their website, the Mercury Prize is classified as the equivalent of literature’s Booker Prize or art’s Turner Prize.[1]

To win the Prize at all is an achievement; to win it for your debut album is astonishing.

But 2021 is a long time ago for Parks. In 2023 she not only released her sophomore album My Soft Machine (Transgressive Records), but also published her debut book of poetry, The Magic Border (4th Estate). It contains both original poems as well as lyrics from My Soft Machine.

There is no apparent correlation between the order of the songs on My Soft Machine and the arrangement of lyrics and poems in The Magic Border. The title itself evokes a disappearing or false barrier between sung words and words destined to be written on, and read from, the page.

This ‘magic border’ both exists and disappears at the same time.

Poetry & Lyrics

The poem-as-lyric or lyric-as-poem is well charted—Parks is not the first to venture into this area. Think about Van Morrison’s two Faber editions of his lyrics (Lit Up Inside (2014) and Keep ‘Er Lit (2020)), for instance, or even Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016 for having ‘created new poetic expressions’. Elsewhere on this blog, I have written about Kim Moore, who is a professional trumpeter as well as an award-winning poet: for Moore, music and writing are intimately intertwined.

But that isn’t my interest here.

I am interested in Parks’s introduction to the volume, where she writes that writing ‘is like uncovering who I am at a cellular level’.[1] Writing discovers the writer, that is, down to the plane of biological metaphor.

There are other differences between poetry and song lyrics. The latter helps Parks to ‘contain and therefore process the world’, while poetry helps her to ‘explore its potential’. This gives poetry a ‘chaotic magic’ (p. ix), suggesting that any illusory border derives from poems rather than music.

A quick glance at criticism reveals pre-existing discussions of ‘cellular poetry’. Sometimes it describes the poetic structure (read: ‘beautiful’) of cells and DNA, for instance. Or, inversely, there is Ben Etherington’s ‘cellular scansion’ of Edward Braithwaite’s Rights of Passage.[2] For Etherington, one idea of ‘cellular scansion‘ is a kind of cultural materialism that offers

a historicized scansion; a scansion attuned to the specifics of any given metrical practice in the terms of the historical condition of the materials of verse being employed, and which seeks to give an account of how a particular poem’s line-cell is able to multiply and flourish.[3]

Etherington’s decolonial practice tries to identify where the natural rhythms of Creolized English (as spoken by various Caribbean citizens) overlay the ‘metrical thoughts'[4] of the colonisers.

But this is still not my ‘cellular’ interest; nor does it appear to be Parks’s.

‘Cellular’

I am instead interested in her poem of the same name. In eight long lines of verse, ‘Cellular’ charts a story of young love and a sick lover. The middle lines describe a ‘Cellular love, diaphanous’, with a poetic persona who ‘liked feeling small in your arms, the weird, feminine shiver it gave me’ (p. 49). This feeling is new and yet also innate—part of the speaker’s biological makeup.

This cellularity emerges in the ‘pink slush of crisis’ and describes a vulnerability but also a defensiveness. ‘I didn’t have the resources to be angry’, we read, as well as the last line that produces a lamentable finality: ‘You decided to protect me, and that was the beginning of the end.’ The vulnerable cellularity of the love exposes the speaker to being looked after, but that creates faultlines between the lovers rather than joining them together.

It is an allusive, metaphorical poem, yet this verbal link between it and the introduction is fruitful. In the introduction, writing reveals the writer; in the poem, the vulnerable, immature speaker discovers something final about her love and about herself. This finality leads to a new self emerging after the end of the poem.

It leads to an analogy in which the sick lover who ‘protected’ the speaker is equivalent to ‘writing’ in general. Writing—cellular writing in particular—becomes both poison and cure.[5]

That this conclusion comes out of one of Parks’s poems, rather than one of her song’s lyrics, is important. Just as the magic border comes out of the ‘chaotic magic’ of writing poetry—a magic that we can now see is a kind of poison creating vulnerability—so too does the border’s overcoming and cure arise from poetry.

[1] Arlo Parks, The Magic Border (London: 4th Estate, p. ix). My emphasis.

[2] Critics traditionally use ‘scansion’ to describe the reading and measuring of poetic rhythm when they identify stressed and unstressed syllables, and work out the poet’s use of metrical feet such as the iamb, trochee, etc.

[3] Ben Etherington, ‘Cellular scansion: creolization as poetic practice in Brathwaite’s Rights of Passage‘, Thinking Verse, III (2013), 186–208 (187) <available at: http://thinkingverse.org/issue03/BenEtherington_CellularScansion.pdf> [accessed 13 December 2023].

[4] Etherington, ‘Cellular scansion’, 189.

[5] These opposing ideas join together in the Ancient Greek word pharmakon. A modern equivalent in English is the word ‘drug’, which can help a sick patient, or bring on an illness.

Leave a Reply