All night a bird beats its wings

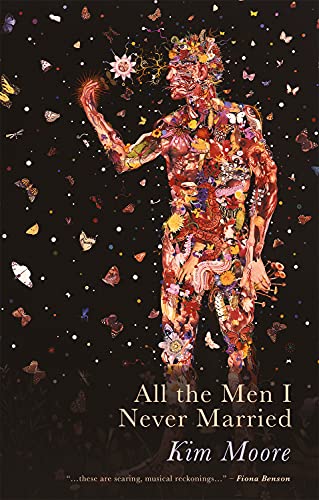

Poem 47 from Kim Moore’s All the Men I Never Married (Seren, 2021)

behind the wall. In the space between rooms

it has the quietest scream. (I realise I cannot live

without desire.) At first I think it’s trapped

behind the wall. Is it another bird

that moves, that seems to fall and rise again?

I am hiding something

in the mirror. In the morning

I am searching for myself

but see a bird rising up behind my eyes.

I think about a girl with hair covering her face

and the bruise of her body and one person listening.

I think about what he said, about the need

to throw a stone behind to catch the one ahead.

The bird calls to me from between the walls.

The bird calls to me from between the walls

to throw a stone behind to catch the one ahead.

I think about what he said, about the need

and the bruise of her body and one person listening.

I think about a girl with hair covering her face

but see a bird rising up behind my eyes.

I am searching for myself

in the mirror, in the morning.

I am hiding something

that moves, that seems to fall and rise again

behind the wall. Is it another bird

without desire? At first I think it’s trapped,

it has the quietest scream. I realise I cannot live

behind the wall, in the space between rooms.

All night a bird beats its wings.

Poem 47 from Kim Moore’s All the Men I Never Married (Seren, 2021), is an award-winning poem. It won the 2020 Ledbury Poetry Competition when it was called ‘All night a bird’, before Moore won the Forward Prize for Best Collection in 2022. An award-winning poem in an award-winning collection: quite a recommendation!

Beginning, ‘All night a bird’, the poem is a mirror poem, or (as has been popularised by poet Marilyn Singer), a ‘reverso poem’.

The ‘reverso’ is a poem that can be read in both directions—down and then up—with the line order totally reversed on the second reading. They are not always printed twice (with the reading order for both readings present), but in the case of Moore’s poem, they are.

Singer recommends that the meaning is utterly changed through the reverso poem, but I wonder if that’s true for Moore. In both versions a mysterious bird—or perhaps two, three birds—are caught trapped in or behind walls.

In the first version, there is also a man who, alternately, talks ‘about the need / to throw a stone behind to catch the one ahead‘, or ‘about the need / and bruise of her body and one person listening’. The first is a sententious idiom about moving forward by giving something up, while the second is about assault—physical? emotional? mental?—on a woman, and the witness to that assault.

It is a disquieting poem, as much about desire (‘I cannot live / without desire’) as it is about being heard when it is difficult to articulate pain (‘it has the quietest scream’). Is the persona trapped? Or is it just a bird? Is the bird a literal bird, or a symbolic bird?

The questions aren’t answered explicitly, so it’s natural to wonder about the significance of the form of the poem. A quick search reveals that these ‘reverso’ poems are considered a rather puerile form of poetry writing—Singer’s books are for children, and there are many school-based exercises for children to practise writing this mirrored poem—and so it’s worth asking whether Poem 47 is faddish rather than effective.

At the heart of both versions is the game of hide-and-seek. In the first version:

I am hiding something

in the mirror. In the morning

I am searching for myself

but see a bird rising up behind my eyes.

And in the second:

I am searching for myself

in the mirror, in the morning.

I am hiding something

that moves, that seems to fall and rise again

behind the wall.

The invocation of the mirror in this poem—a poem that formally manifests the mirror—invites the reader to consider the power of the image.

The mirror becomes central to understanding the poem and the persona’s self-discovery. This self-discovery is offset or deferred on to a bird. We are also invited to question whether the persona is complicit in the denial of self-knowledge, when they write that ‘I am writing something / in the mirror’ first, before ‘I am hiding something / that moves’.

Has something taken place between the two versions? Or are they simultaneous reflections on the same preceding event, prior to the poem’s narrative? Is self-discovery harder in the second version or just the same?

I worry and wonder whether this poem’s form precedes—and superseding—content; or perhaps it’s just me, finding it tough to pierce the poem’s formal shell.

Leave a Reply