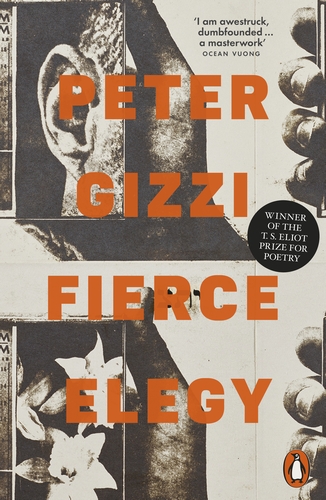

In Fierce Elegy (2023), Peter Gizzi’s 2025 T.S. Eliot prize-winning collection of poetry, the poet does many astounding things. These include his use of form, the contiguous suturing of images, and—as I will briefly show—his elaboration of space.

Spatial forebear

While I was reading Fierce Elegy I was reminded of the early modern English poet, John Donne (1572–1631). In a 1957 essay, English literary critic William Empson called Donne a ‘space man’.1

Empson’s point was that Donne incorporated some kind of desire to travel to another ‘planet’—though the words Donne used were not always planetary in nature.

Empson wrote this essay on the cusp of the space race, just three years before Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space.

But there is something else in the way Donne treats space that is significant, and has always inspired me. Take the following lines as a representative example:

We can die by it, if not live by love,

And if unfit for tombs and hearse

Our legend be, it will be fit for verse;

And if no piece of chronicle we prove,

We’ll build in sonnets pretty rooms;

As well a well-wrought urn becomes

The greatest ashes, as half-acre tombs,

And by these hymns, all shall approve

Us canonized for Love. ('The Canonization', ll. 28–36)

For Donne in this poem—as elsewhere—space is expansive and accommodating. He is already overturning in anticipation the fixed Newtonian concepts of space and time. For instance, Donne will ‘build’ in sonnets ‘pretty rooms’, the idea being that poetic space is flexible enough to create anything of any size.

On one level, this poetic idea must seem commonplace: poems describe all sorts, including ‘pretty rooms’ or ‘legends’ that far outsize the length of the poem.

But on another, I find astonishing the way that Donne’s speaker is willing to use poetic space as a strategy. It becomes a political and personal tool to woo women, but also offers utopian possibilities: poetry can extend as far or as near as you like, and can hold as much or as little as we need.

Poetic space can be dense as a black hole, or empty (waiting to be filled) like air.

Donne’s strategy is, as we should hope, the archetype of ‘metaphysical’ poetry.2 And this is the kind of spatial ballet I read in Gizzi’s elegies

Gizzi the space man

I don’t want to spend time exploring the ‘meaning’ of Gizzi’s poems—not least because I’m still working through them for myself.

However, a couple of images call out to me and remind of Donne.

For instance, this is from ‘Dissociadelic’:

To be a desperate player

in the invisible world.

This is something different.

To have crossed over into ink

and to loiter and bleed out

on the occasion of the universe.3

Or the quantum science-referencing poem, ‘Spooky action’:

I want to use all the words tonight.

Words to open the backseat in the discourse.

Words to dilate and amplify the total disco night. (p. 45)

There is a subtle difference in the two poets’ use of this magical, metaphysical space. Donne’s is playful and strategic; but Gizzi’s is exploratory, as if discovering space and its possibilities for the first time.

And, in that way, Gizzi has become the new space man.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.