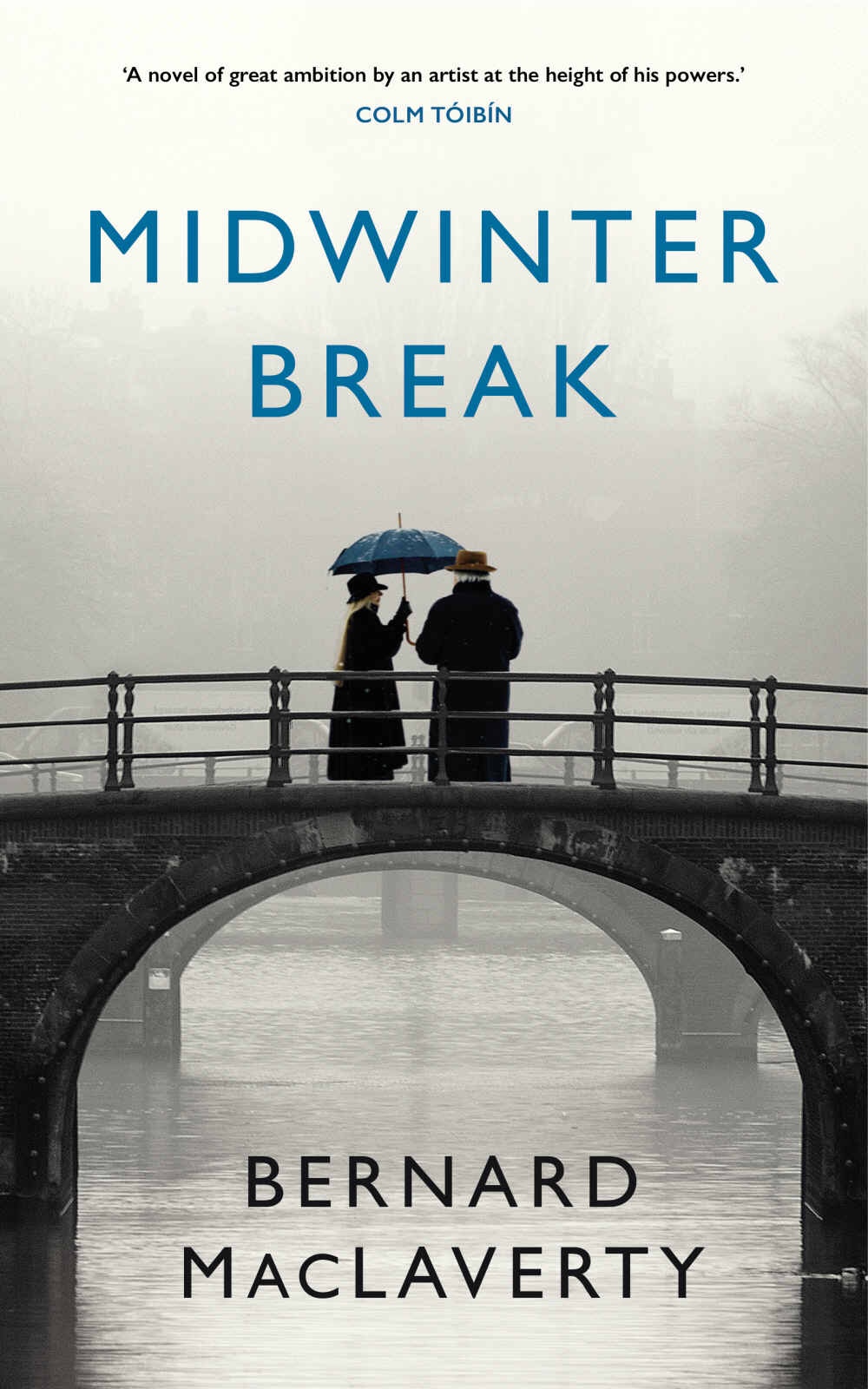

I toyed with the title of this blog. It could easily have been titled ‘Love in Amsterdam’, because the novel is mostly about a third-age love story between husband Gerry and wife Stella who go on holiday to Amsterdam.

But Bernard MacLaverty’s Midwinter Break (Jonathan Cape, 2017) is shadowed by a hazy story of tragedy in Troubles-era Derry and Belfast. The events of ‘that night’ punctuate the trip to Amsterdam through flashbacks in both characters’ narratives. Belfast and Derry are dimly present in the long weekend trip away, firmly turning this book into another in the long litany of texts that detail the consequences of the civil war in Northern Ireland.

Midwinter Break is also a story of migration. Following the tragedy in Belfast, the couple move to Glasgow where stories of the Troubles are not so fascinating to the locals as they were in Northern Ireland. To migrate in this case is also to start again afresh.

The same can be said of the trip to Amsterdam that, on one hand, is a chance for the couple to enjoy their retirement pot, but on another is an opportunity for Stella to explore options for becoming a Begwijn, a devotee to the Catholic Church. This is akin to becoming a nun, but without the restrictions of celibacy. Stella’s interest in changing her lifestyle so wholly is also a result of the attack in Derry and a promise she made to God. Thus the trip to Amsterdam, like the move to Glasgow, is about wiping the slate clean.

There have been other recent migration narratives in Irish literature, one of which I have written about on this blog. Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangiers was wholly different in tone to Midwinter Break, but also used the migration narrative to highlight the importance of (trying to) start afresh in a new place or new country. I also have Anne Enright’s Green Road in mind that, whilst not wholly convincing as a work of art, also sought to describe an Irish family’s global dispersion. For those family members, flying the nest represented one way of escaping their mother’s Lear-like control over their lives.

These stories tell a commonly told tale of Irish emigration. Ireland has long been a nation of émigrés, so this is nothing new. However, coming amid the backdrop of a rise in global movements, largely a result of displacement of peoples after war or political turmoil—think of Syria, for example—these contemporary Irish migration stories localise the drama of migrating and the heavy psychological baggage that comes with it.

Combined with the Troubles narrative, Midwinter Break offers something far different to, say, Anna Burns’s Milkman, that roundly heralded Booker-winning novel. McLaverty’s prose is lyrical and gentle where Burns’s is labyrinthine and dense; the story is plain where Milkman’s is deeply traumatic and confusing. Midwinter Break is much more about the characters than the city, and a great deal of joy is dished out in giving Stella and Gerry their characters, warts and all.

The novel’s end is broadly inconclusive, but the simplicity of the prose finally finds a chance to offer the intense vision that the story was always leading to:

He tried to build a picture of this landscape before the snow. […] Thousands of years before that—marshlands with sedge blowing and water reflecting the brightening sky. The sound of birds. Curlews flying from horizon to horizon in great circles. Flocks of waders rising simultaneously and explosively to meet the day. In such places people had been sacrificed, strangled, thrown into the fen and forgotten. Survivors’ funerals.

Bernard MacLaverty, Midwinter Break (London: Vintage, 2018 [2017]), pp. 242–3

The prose here enters a lyrical register occupied by Seamus Heaney in his bog poems from Wintering Out (1971) and North (1974), which best characterises the submerged though persistent Troubles narrative in Midwinter Break. Perhaps Heaney, rather than Enright or Burns, is therefore the best guide for how to read the novel.

It’s not bad company for MacLaverty to keep, either.

Leave a Reply