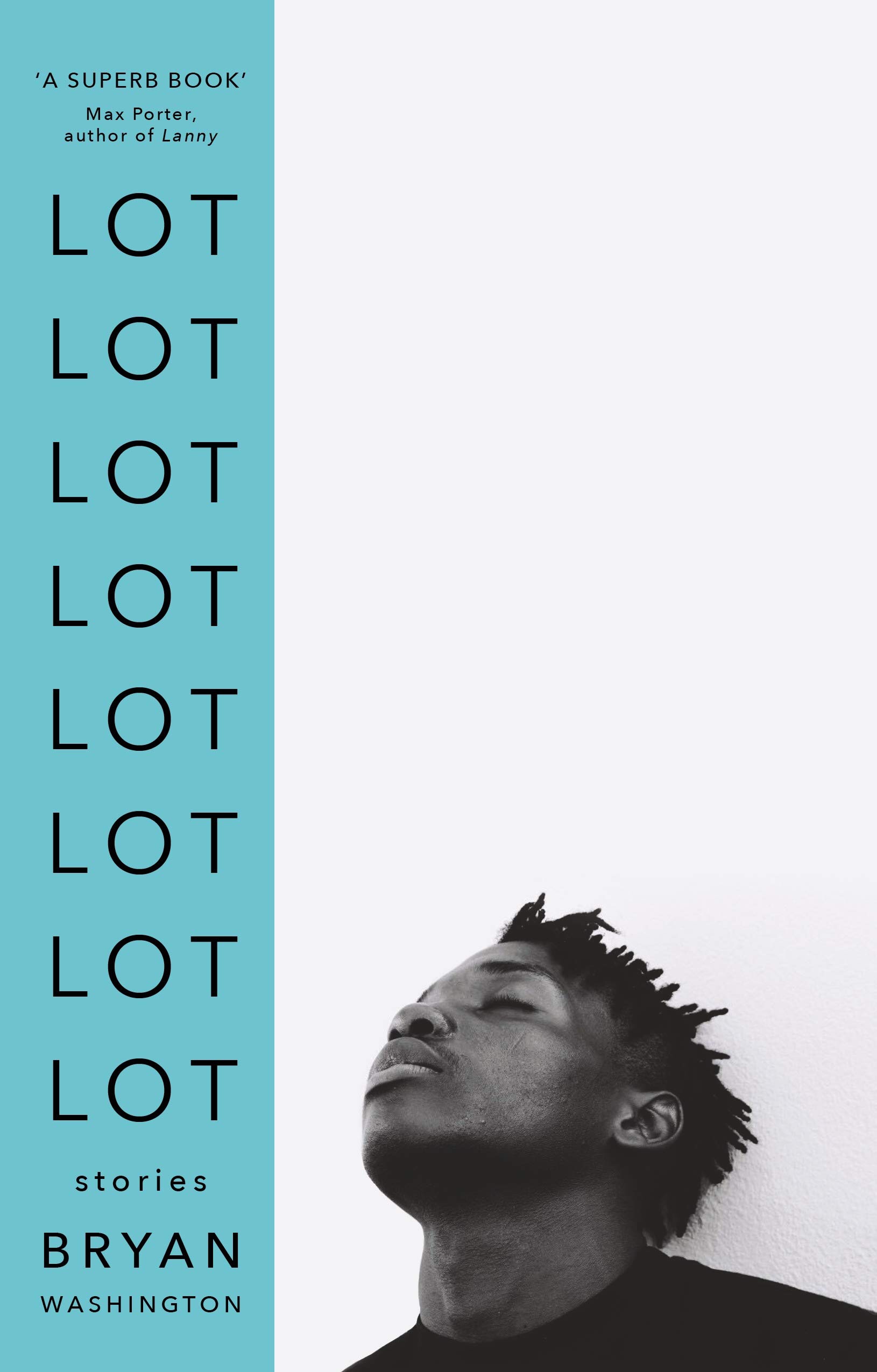

Bryan Washington’s Lot (Atlantic Books: 2019) is a short-story collection depicting the lives of several Houston citizens. One character’s story recurrently comes in and out of focus throughout Lot, but otherwise the stories transition between characters—mostly men—and explores how they experience the city.

Another key element of the collection is its focus on who we’d call in Britain BAME characters. Lot documents the undocumented in the US, notable especially because Texas, where Houston is located, is a border state with access to and from Mexico. Moreover, many of these male characters are also queer, thereby pushing their lives and stories even further into the margins. We read stories of male prostitutes, of migrant workers, and of kids’ baseball games in the park.

Lot is in a battle for the ordinary, trying to tell common and garden stories of lives that, for some, are anything but ordinary. Lot tries to make being queer less queer (in the sense of unusual), and tries to domesticate the stories and lives of those officially unwelcome in the domestic US territory.

The stories are given titles of places in Houston where the action takes place. For example, in ‘Navigation’, a waiter goes home with one of his restaurant’s customers who ‘lived in a condo on Navigation’ (p. 134); ‘610 North, 610 West’ gives the address of the narrator’s father’s mistress; and the title story ‘Lot’ is about the protagonist’s home lot that his mother is trying to sell to capitalise on the slow gentrification of the East End where they live. The book is a map of the city of Houston, reminiscent of Irish poet Ciaran Carson’s ‘The Irish for No’ (1987) and ‘Belfast Confetti’ (1990)—I mean this as high praise.

The battle for the ordinary also takes place in language. The narrators’ syntax is commonly staccato with lots of sub-clauses. As a random example, see the following from the end of ‘Alief’, a story of infidelity with a fatal end:

Aja was Aja and Paul was Paul and James was James and James was Paul and Aja was James and they were us, and we retold it, remixed it, we danced it from the stairwell, and we hung it from the laundry, and we shook it from the second floor, until our words had run out, until our music ran dry, and Five-0 shut it down on account of the noise.

Bryan Washington, ‘Alief’ in Lot (London: Atlantic Books), p. 21

Not only does the story refuse to translate ‘Five-0’ (slang for the police), but the syntax is disruptive and vernacular. Throughout Lot, Washington’s narrators speak their own language—be it English, Spanish, Spanglish or apotheosis—and make no attempt to sanitise their language or its stylistic quirks for the readership. They are battling for an ordinary.

The idea of the battle for an ordinary comes from queer feminist and race campaigner Sara Ahmed. This battle is about queer representation and entails ‘remember[ing] a scene that has yet to happen, a scene of the ordinary’.[1] I think that in Lot, Washington’s characters successfully manage to win the battle for their queer and raced ordinariness.

For instance, in ‘Navigation’ when the recurring narrator’s lover ‘asked if I was out’, he responds that ‘I didn’t know what that meant’ (p. 138). Here the ordinary battle is over what it means to be queer, with the narrator battling through language and a speech act (i.e. the ability to say/not to say whether or not he is queer) for his ordinary: to be gay is (merely) to be.

The recurring narrator is only named in the final pages in the final story, ‘Elgin’. This ordinary gesture of naming finally catalyses something for the narrator, and he is able to undertake a journey that takes place as much through a philosophical landscape as through Houston’s cityscape:

I make it out of the Ward. The city’s silhouette dims. […] This is the furthest I’ve been from the city, my city, in years, but it doesn’t feel like anything’s changed, and honestly, why would it. You bring yourself wherever you go. You are the one thing you can never run out on.

Washington, Lot, p. 221

The individual self, the ordinary self, is mundane in its permanence for the narrator. It confers on the city a similar stability (‘it doesn’t feel like anything’s changed’) that in turn anchors the narrator in place. This is Lot’s queer self; this, too, is the queer and vibrant city of Houston. You can find the ordinary in its margins.

[1] Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), p. 222.

Leave a Reply