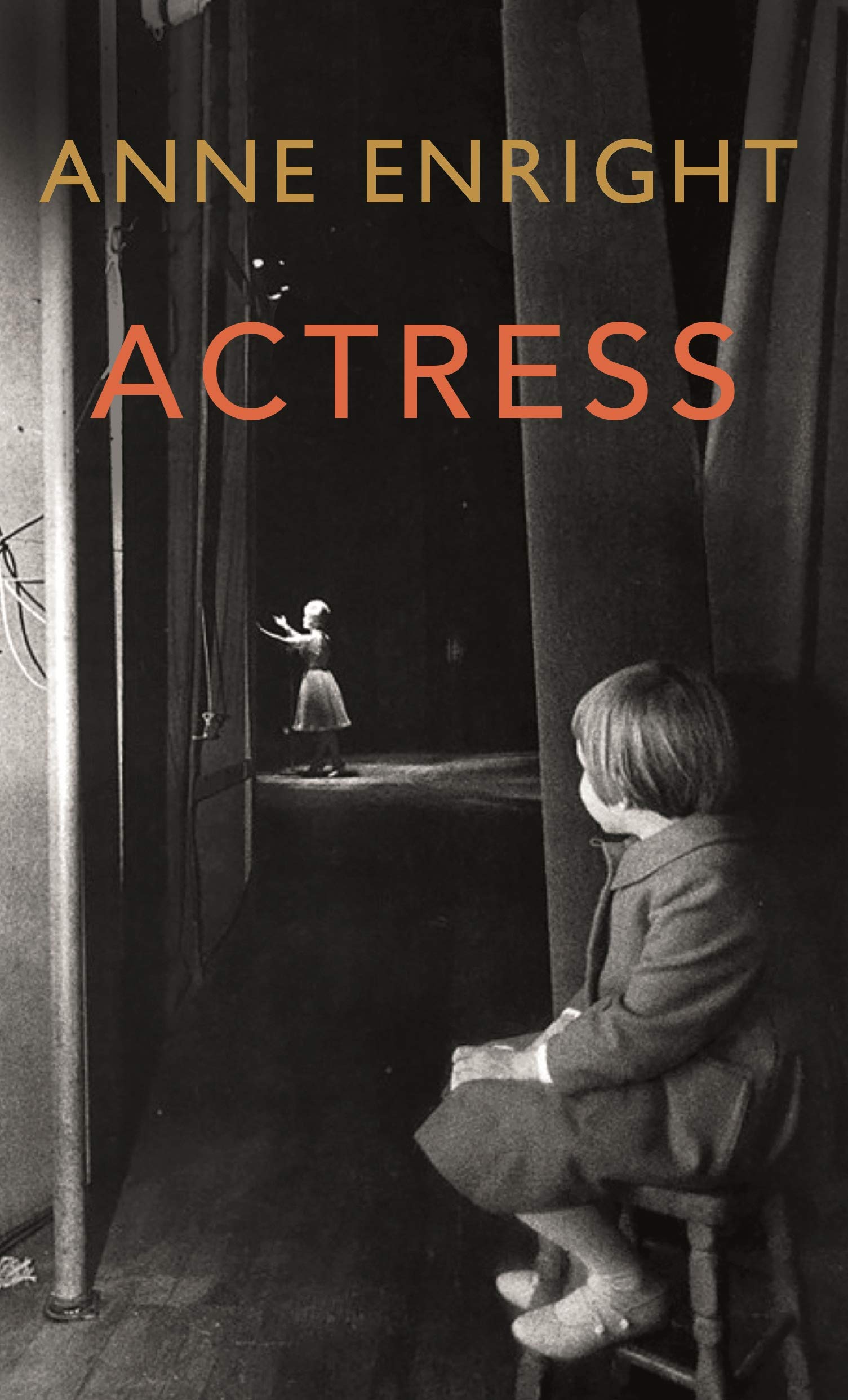

In my first blog on Anne Enright’s Actress (Jonathan Cape, 2020), I connected it with the late Irish poet Eavan Boland (1944–2020) through the search for a female genealogy. Or, in simpler terms, both Norah in Actress and Boland in her prose and poetry are looking for their mothers.

In this blog, I again read Actress alongside Boland’s prose writing from A Journey of Two Maps (2011), and this time reflect on the urgent, and urgently contemporary, discourse of consent in sexual relations. The question of sexual consent has been in sharp focus over the past few years, spurred on by the #metoo movement and the belated social awareness of the importance of explicit consent in matters of sexual intercourse.

Only a fortnight ago, the British court of appeal ruled that a man with learning impairments could not use his failure to understand the notion of consent as his defence against claims of sexual assault. Consent is moving away from learned behaviour to the far stronger legal position of ‘right’.

In the Irish context, consent has been closely linked to the #Repealthe8th protest movement, which focused on restoring to women their rights over their own bodies with regard to abortion availability in the Republic of Ireland. This successful campaign—the Eighth Amendment to the Irish Constitution was repealed after a referendum in May 2018—found a voice across the Irish cultural spectrum, but not least in books like Louise O’Neill’s Asking for It (2015). O’Neill, born in 1985, is of a younger generation to both Enright and Boland. We could be forgiven for thinking that the debate about consent is a young person’s game.

Far from it: Boland and Enright deal with the issue, albeit in different ways.

In Actress, Norah reaches sexual maturity while at Trinity College in Dublin. After she graduates, she sleeps with a former English professor. On the second occasion, however, the whole evening has a different tenor to the first:

There were two moments that evening when something loosed in me, or gave way. The first was three quarters of the way down my second glass of Harp, the second was at the side of his bed, with the edge of the mattress pressing into the hinge of my knee, when my protestations had continued to fail.

(In Ireland, as I sometimes explain to foreign-born friends, you always refuse a cup of tea. […])

Perhaps this is why I helped Niall Duggan with my underwear.

Anne Enright, Actress (Jonathan Cape: London, 2020), p. 183

Unnervingly passing off Duggan’s attempt at bedding Norah as idiosyncratic Irish behaviour, Norah seems to be content with the lack of given consent.[1] The remainder of the book, and especially the scenes that follow (including her mother Katherine’s degradation into mental instability), find some kind of root cause in Duggan’s rape of Norah.

In Boland’s essay the story of consent emerges in a different context. Boland writes about her own mother who was a fine artist and narrates an occasion when, in an art gallery, Boland unexpectedly comes across one of her mother’s own paintings. However, rather than her mother’s name in the corner of the canvas, Boland finds her mother’s teacher’s name. What plagues Boland is not only that her mother

had let him sign it. It was not the signature that shocked me; it was that consent. Down through the years, from a time when I had not even been born, came that faint yes.

Eavan Boland, ‘A Journey with Two Maps’ in A Journey with Two Maps (W.W. Norton: New York, NY, 2011), loc. 253–4

This double revelation—of both her mother’s teacher’s deception, and her mother’s tacit acceptance—is instructive to Boland in how women often fail to find their rightful place in narrative history. Boland’s reflection on her mother’s consent is informed by the 1920s Paris context in which her mother was learning her trade as an artist. The implication is that, whilst we are now in the ‘age of consent’ as it were, women in 1920s Paris did not have the luxury of saying ‘no’. The ‘faint[ness]’ of her mother’s consent already constitutes some kind of resistance.

If, for the older generation, the act of giving consent wasn’t considered a mode of sexist redress, then Boland’s reading of her mother begins to resist this. Likewise in Actress, with Norah’s reluctant discussion about consent through the metaphor of tea, it is perhaps implied that the older generation—1970s Ireland for Norah—have neither the inclination nor vocabulary to think about consent as a way of protesting women’s bodily rights.

However, like Boland, Norah is herself surprised by the discovery of her mother’s writings from the 1950s. Among the papers she finds, Norah discovers that she and Katherine have both experienced rape. Norah (as I detailed) at the hands of her ex-teacher, and Katherine from an unnamed man who becomes Norah’s long-undiscovered father:

when I was twenty-three years old

and an adult woman

I was

by a man called

and I

woke up with

I went away with

my baby my baby

because I wanted something to hold

He said that I had learned to be a good girl

He said I was a bad

He convinced me I

Where do I go from here

I tried clenching my vagina shut[.]

Enright, Actress, pp. 230–1

The fractured, incomplete sentences and the line breaks clearly signal Katherine’s inability to verbalise her experience of rape. Not unlike Norah, speech bears the scars of abuse. For Katherine it’s syntactical incoherence; for Norah it’s digressive circumlocution via a cup of tea. In my previous blog I argued that Norah’s search for her father becomes a discovery of her mother. I now want to suggest that, via the discussion of consent, Norah’s discovery of her mother is also a rediscovery of her connection to her mother, and therefore a rediscovery of herself: they have both been raped.

Consent, in the context of both Boland’s essay and Enright’s novel, is not so much about the fourth-wave feminist activism that it is today for writers like Louise O’Neill. Instead it is associated with finding oneself, and finding a place for oneself within a female genealogy. I’m not suggesting a hierarchy between these attitudes and processes, but I do think it’s worth noting that Boland (b. 1944) and Enright’s Norah O’Dell (b. 1951) are fighting the same fight as today’s feminists, but that their endgame differs.

[1] Is Enright aware of the online campaign that seeks to explain consent via the practice of tea drinking? See the video below for an example:

Leave a Reply